Soul of the Sahara

As one of the few players of the Touareg fiddle visits London, Simon Broughton travels to the Sahara to discover the desert power of gourd and goatskin

“For the Touareg the imzad is like a sacred instrument,” says Alamine Khoulen (also transliterated Alamin Khawlen), one of the most venerated players from the middle of the Sahara. "In our nomadic culture the sound of the imzad marks a resting place. You can't go past, you have to stop." You can imagine long evenings round a fire in one of those camel-skin tents with endless cups of sweet Touareg tea and the hypnotic sound of the one-string fiddle carrying you through the night.

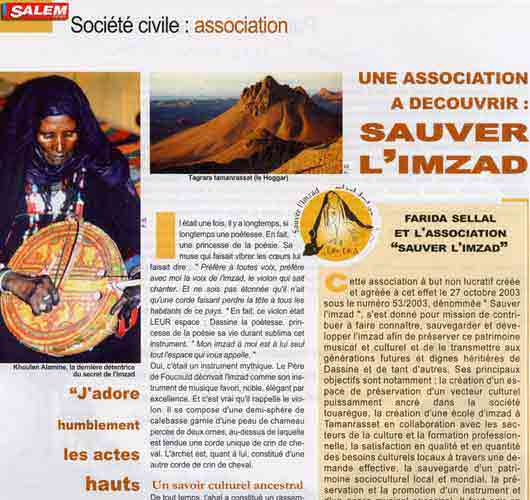

The Touareg are the proud, nomadic traders of the Sahara and number one-and-a-half million across Mali, Niger, Burkina Faso, Libya and Algeria. They are distinctive in many ways from their neighbours in North Africa and the Islamic world. The men are heavily veiled, often with little more than their eyes visible, while the women wear a headscarf but keep their faces uncovered. And traditionally, wherever you find the Touareg, you find the imzad, which is exclusively played by women. As Boukeyass Nighat, the poet who performs with Khoulen, puts it: "The imzad is so sacred that only women can touch it. Nobody can touch our imzad and nobody can touch our women, they are one." The musical relationship between imzad and poet is an unusual one. The imzad is no mere accompaniment, it leads. "The imzad has a voice," Nighat explains, "and I am inspired to create the poetry as I hear the music."

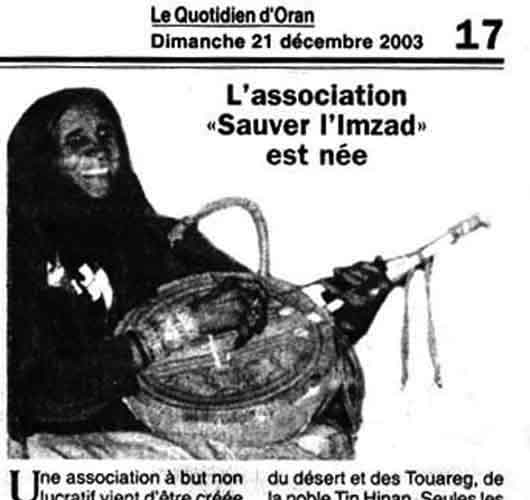

Alamine Khoulen, from Tamanrasset in the Hoggar mountain region in the heart of the Sahara, unties a chunk of resin from her headscarf and rubs it onto the horse-hair strings of her bow. Each of the bony fingers of her left hand is incised with a groove after probably 60 years of pressing them against an imzad string. It may be a simple instrument, made from a calabash gourd covered with goatskin, but it has an enchanting quality – particularly as you focus in on it. Khoulen keeps her hand in one playing position, but the limited scale is coloured by rough, scratchy harmonics that bring a spectral, magical element to the sound. It ranges from the reflective to the transcendental. As if indicative of their power, most imzads are beautifully decorated. Alongside the intricate painting in red, yellow and green, the one Khoulen is playing has an inscription in the Tifinagh alphabet saying 'The imzad of Hoggar, keep it alive!'

Inevitably, as Touareg society changes, opportunities to hear the imzad are dwindling. At the Festival of Saharan Tourism held in Tamanrasset over New Year, Alamine Khoulen was honoured in the speeches before a VIP platform, but the instrument was inaudible in a street procession. In Algeria, aside from Khoulen, there's another venerated player, Tarzagh Ben Omar, from the Janet region. The excellent Malian group Tartit feature an imzad alongside the tindê drums, also traditionally played by women. In an effort to save the imzad and its tradition, 0 (www.imzad.org) was founded in Tamanrasset last year. The organisation has opened a school with seven imzad players and makers and they've just held a three-day international colloquium on the instrument and its place in Touareg culture. The crucial question is whether a younger generation will identify with the imzad as Nighat does: "It gives me pride and courage as a Touareg. It's my pulse and I can't live without it."'

----**----

Alamine Khoulen and Boukeyass Nighat appear at the Queen Elizabeth Hall on April 23 in a double bill with Algerian Gnawa musician Hasna. Farida Sellal, the chairperson of Sauver l'Imzad, is also giving a lecture.